For the last year, I’ve been cultivating a small oyster garden in NYC Harbor as part of the NY/NJ Baykeepers oyster gardening program. It has been a journey full of unexpected delights, failures and mysteries.

This year, the oyster gardening program has been rolled into the Billion Oyster Project, an initiative run by the Harbor School Foundation. The Billion Oyster Project works with students and teachers in NYC to educate them on the ecology and economics of their local watersheds. The goal is to restore one billion oysters back to New York Harbor within 20 years. If that sounds like a grand, impossibly lofty undertaking, consider that oysters once covered hundreds of miles of shoreline along the Eastern seaboard, and after European colonists arrived, more than half a billion oysters were harvested each year through the first half of the 19th century! So restoring a billion oysters back to their historic home is really a drop in the bucket compared to the teeming masses of oyster reefs that used to line the harbor.

My first task was to remove last season’s oysters from my cage and return them to the Billion Oyster Project. This is what 300 juvenile oysters in a backpack looks like:

In the past, there have been concerns raised by local governments about the safety of the oyster gardens and their vulnerability to poaching. Oysters raised in NYC Harbor are not safe for consumption, and the fear is that someone might try to steal and resell the oysters. NJ even went so far as to ban all research-related shellfish gardens. To alleviate some of those worries, this year the Billion Oyster Project is moving to using oyster shellstock (clusters), rather than oyster singles (the nicely manicured single oysters you see at the raw bar).

Here, you can see that small, thumbnail sized oysters have settled on larger pieces of oyster shell. As the oysters grow, they won’t be as pretty as oyster singles, but they will be equally valuable in cleaning and filtering our waterways. The clusters are also perfect for Southern-style oyster roasts.

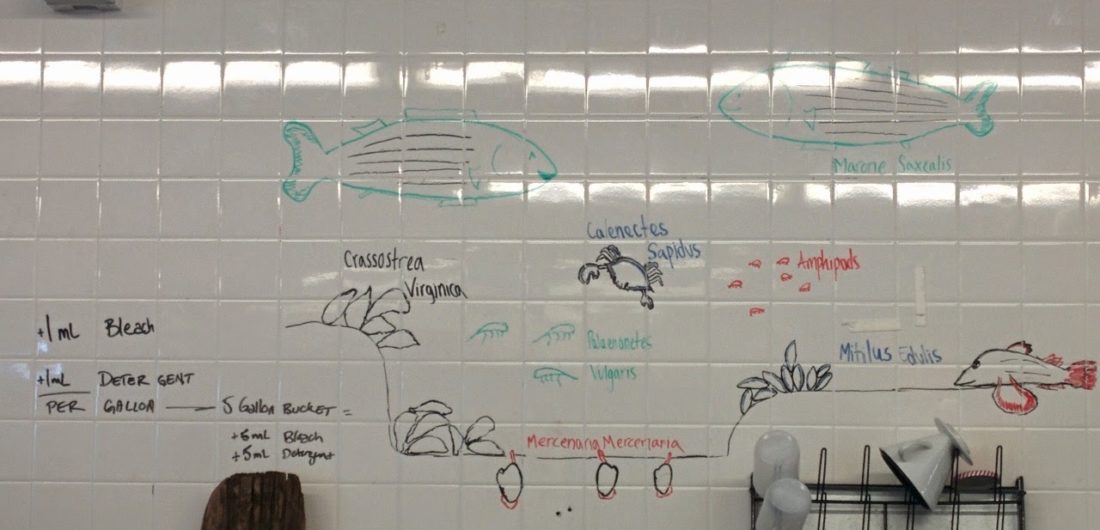

The Billion Oyster Project and Harbor School is headquartered on Governor’s Island, where New York City’s first and foremost oyster hatchery is located. After volunteers arrived for oyster garden training day, Sam Janis led us on a tour of the facilities.

Inside these quietly burbling tanks, 5 million oyster larvae were looking for places to set. And what’s the best place for an oyster to settle? On an oyster! It makes sense that if another oyster were successful in a given location, another oyster would do well in the same area. Plus, it’s easier for oysters to spawn and fertilize larvae if they are located near other oysters. To mimic those natural conditions, bags of cleaned oyster shells are placed in the setting tank, where they’ll attract microscopic oyster larvae.

So, what do you feed growing oysters? You might remember from our tour last year at Taylor Shellfish’s hatchery that every hatchery not only grows oysters, but algae. Here, you see the algae tanks that will be used to keep the oysters full and happy.

After touring the facilities, we all got to work building oyster cages. I was never expert at arts & crafts as a kid, and quickly screwed up my oyster cage by cutting off 2 extra inches on the first panel. Oops. Luckily, metal is malleable and we were able to MacGyver a fix for my asymmetric (but still functional!) oyster cage.

Afterwards, we each counted out 300 oysters for our cages and were given instructions on how to log our data and use the water quality monitoring kit. With my new oysters in tow, I returned to my cage site and dropped the oysters into their new home. I also shortened the rope a bit to raise the cage further away from the seafloor (and predators).

We’ll see how this year’s oyster crop goes!