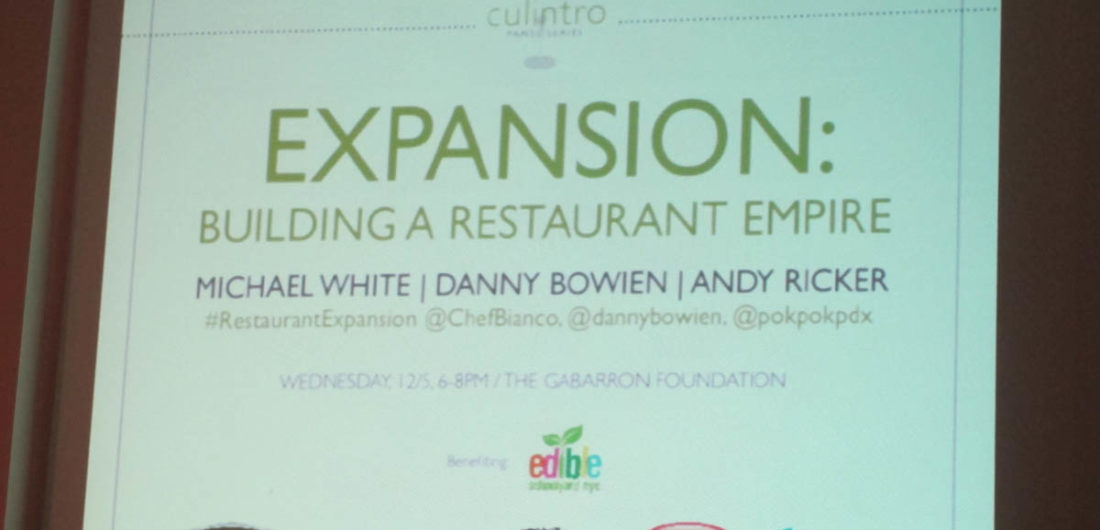

So you’ve created a wildly successful restaurant, and you’re just beginning to have some semblance of stability and free time again. Is it time to expand and build another location? At last night’s Culintro panel on restaurant expansion, three prominent chefs tackled that question and more. Danny Bowien (Mission Chinese), Andy Ricker (Pok Pok) and Michael White (Marea, Ai Fiori, Osteria Morini, Nicoletta) collectively shared their insights and mused on why anyone would decide to “go do the hardest thing in the world—open a restaurant in New York.”

After all, opening and running a restaurant is asking for unexpected kinks and surprises every day. “You wake up in the morning wondering if today is the day you get your ass handed to you,” Ricker noted wryly. “The job is basically problem solving. It’s being able to grasp a whole lot of things happening at once.” That global vision is what makes a chef and restauranteur. “It’s not just cooking—you’ve got to know about electricity, basic engineering, and when something breaks, you can’t call someone because he’ll come three hours later and you need it fixed now.” Bowien agreed and offered some optimism: “All the challenges—if you can just power through them, it’ll work out. When we were getting reviewed by the New York Times, I was flying back from Copenhagen, and just after I landed, someone texted to say the New York Times is here…and so is the health department. I was having a heart attack! But you just have to power through it all.”

So when do you know it’s time to expand? Most people don’t set out to build restaurant empires, but it becomes clear when the timing is right to grow. “When your restaurant is very successful, you have a sort of political capital, and you either spend it or you don’t—you sh*t or get off the pot,” said Ricker. “You reach a point where you have ideas that don’t fit in the current template. If there’s interest and political capital, the door just opens up.” Over the course of the evening, Ricker, Bowien and White batted ideas and shared the following lessons for aspiring chefs and restauranteurs (or any entrepreneur):

Danny Bowien, Andy Ricker and Michael White

Take care of your employees: You can’t grow your business without help. “It’s all about the people that work for you,” said White. “Marea has 149 employees; it’s those people working very hard every day, carrying out your vision. I couldn’t be here tonight if I hadn’t worked very hard for the 15 years before this.” Bowien explained that he knew his restaurant in San Francisco was in good hands because he’s worked with the chef for 10 years. “It’s about finding those people and holding on to them,” he said. Doing so requires taking on much more responsibility, far beyond what’s required as a line cook. “It’s like growing up,” said Bowien. “Being a chef is knowing you have people you’re responsible for, and that you have to pay them so they can support their families.”

Get it right from the beginning: In an era of trend-focused food media, Yelp and blogs, it’s crucial to start on the right foot. “You don’t have a lot of time to get it figured out,” said Ricker. “The critics are there right away, your rent is through the roof, and you have very little time to get your poop in a groove group*.” Having strong media presence is great, but only if you have substance to back it up. “If you come in with a lot of PR and you suck, it’s even worse—it’s like you suck squared,” said Ricker.

Be a neighborhood restaurant: In the end, once the buzz has died down and the bloggers are no longer rabid about your restaurant, you have to understand your market and neighborhood. “I know it sounds crazy,” said White, “but Marea is a neighborhood restaurant. We have people who eat there 3x a week.” These are the people who will support and sustain your business once the media attention has faded. “There’s people who own multiple restaurants and never get media attention,” said Ricker. “And they’re very, very successful restauranteurs.” In the end, it’s all about the customers calling the shots. “You just have to be really f***king nice,” said Bowien. “If they want to pay for it vegan, we’ll make it vegan.” Ricker advocated diplomacy: “You have to find a way of saying no by saying yes.”

Embrace technology: In an age of web apps and smartphones, it’s no surprise that technology was touted as a way to manage far-flung business locations and global staff. Skype and Google Docs were mentioned as tools to ease communication and share information. Bowien described his more unorthodox method to connect his kitchens: “We have the ghettoist system—Thomas Keller has TV screens in his kitchens where they can talk to each other, so we thought, we can do that. We bought two iPads, set them on FaceTime full-time, Saran-wrapped them and taped them to the wall!” Of course, technology is only valuable if it works for your business. “Technology is not the ultimate answer,” Ricker cautioned. “It always has unintended consequences.” He explained that at Pok Pok, “We on occasion have a wait, so we have a system to get our diners back by texting diners. But what we didn’t anticipate was diners not having good reception, or not checking phones, so we’d call them anyway. Plus, people thought it was too impersonal. So we stopped using it.”

In the end, while the challenges are vast, the rewards of running a restaurant (or five) are immensely satisfying. “I pinch myself every day,” said Bowien. “I still dork out when I run into Wylie [Dufresne] on the street–I’m saying, ‘Oh my god!’ When we came to New York, we didn’t have an agenda, we just didn’t want to fail.” I think we can all agree that these three chefs are not only succeeding, but pushing the limits of restaurant ownership to unprecedented heights.

*Post has been updated to correct a misheard phrase. Apparently the colloquialism is “poop in a group”–I’m unfamiliar with this and apologize for any confusion about Andy Ricker’s septic system.