We’re going to dive into the nitty gritty of what an oyster farmer does, but first, we should understand how oysters grow in the wild, so that we can better compare the oyster’s natural life cycle to modern aquaculture techniques.

Picture a sunny, early summer day. Temperatures have been steadily climbing and the water has gone from a frigid dip to a warm bath. The rise in temperature triggers oysters to begin spawning, creating reproductive material. The exact temperature varies between species, but it’s about 68 F to trigger spawning for the Eastern oyster species.

Oysters put a considerable amount of effort into spawning, and in fact, most of the oyster’s body will turn into eggs or sperm. A European Flat oyster creates about 1 million eggs, while the Eastern oyster produces 15-115 million and the Pacific oyster produces 60 million. Most oysters are broadcast spawners (including the Eastern and Pacific oysters), and release large clouds of eggs and sperm into the water to be fertilized. There are some types of oysters (such as the European Flat oyster) which are brooding spawners, in which male oysters release sperm into the water, and female oysters filter the sperm out and fertilize eggs held internally. The fertilized eggs are then able to grow and develop a bit more before being released into the water, which comes at greater cost to the parent oyster, but also affords the larvae a higher survival rate.

If you’re wondering how to spot a spawning oyster, it’s usually pretty clear. As in, the oyster’s body goes from being opaque to translucent, almost watery in appearance. What if you eat a spawning oyster? It won’t hurt you, but it also won’t taste very pleasant, and will be highly acidic and thin. (Spawning has traditionally been one of the reasons people don’t recommend eating oysters in the summer, though this is no longer true in modern times.)

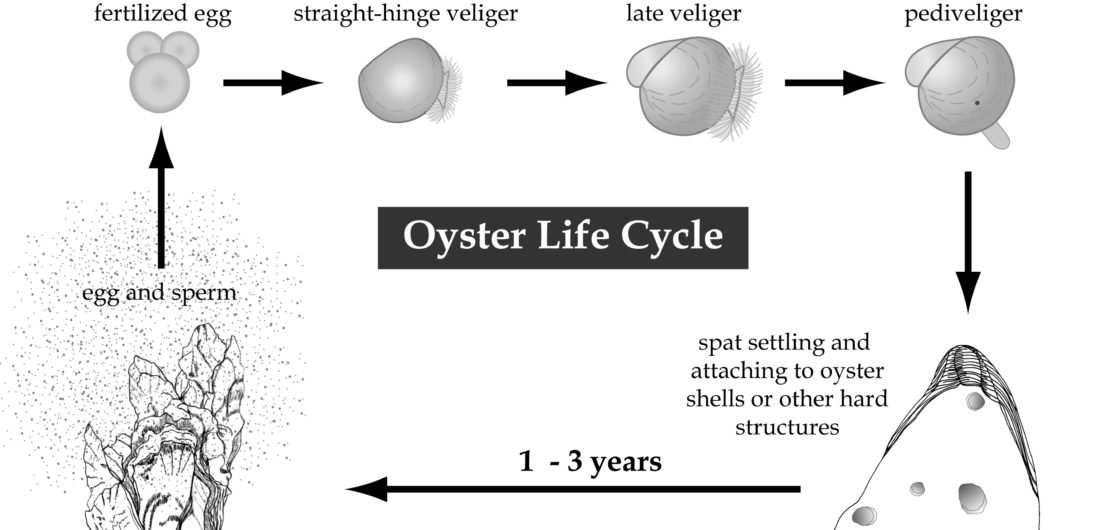

Once the egg is fertilized, it begins to divide. It becomes a trochophore, with hair-like structures called cilia, to help it move in the water column and search for food. In the veliger stage, two shells develop and an organ called the velum forms, allowing for feeding and additional movement.

The free swimming larval oyster develops a foot and an eye, and at this stage, it is called a pediveliger. Yes, that’s right, at one point in their lives, oysters move freely and have an eye and a foot! At this point, the oyster needs to look for a surface to attach to. Oysters in the wild will attach to any hard substrate, including rocks, driftwood, piers and more. What’s the ideal substrate? Another oyster! This indicates that there’s enough algae and water circulation to support an oyster to adulthood, so it makes sense to take your chances at a location where other oysters have thrived. Thus, oysters often settle on top of each other to form oyster reefs.

Once the oyster sets on a substrate, it is called spat. Later on, it becomes a juvenile oyster, and continues to grow and remain in this stage until adulthood, when it is able to reproduce.

Oh, one more thing, oysters are born with a particular sex, however they can switch between male and female. (Wouldn’t it be handy if humans could do the same?!) Many oysters begin as male, then become female as they age, however some can change their sex from year to year as sequential hermaphrodites.