Some light conversation fodder for a cocktail hour? Not so much. I was attending a roundtable discussion at the 2016 Social Good Summit, a conference that examines the impact of technology on socially beneficial initiatives around the world. The summit coincided with the annual meeting of the United Nations General Assembly, and unsurprisingly, the speaker list was studded with world politicians, humanitarians and celebrities. Actor Alec Baldwin spoke about the need to empower indigenous peoples to protect tropical forests, and Vice President Joe Biden received a standing ovation for his “Cancer Moonshot” goal to cure cancer. However, some of the most poignant moments came from ordinary people who had accomplished extraordinary things, like Memory Banda, a young lady who escaped the scourge of child marriage in Malawi, and worked to convince 60 chiefs to pass bylaws banning the practice in their villages.

Back at the roundtable, we were introduced to the morning’s topic (“Brainstorming a Food System Shift: Emphasizing balanced, sustainable suppliers”) by Greg Shewmaker and Brent Overcash from Food+Future CoLab. A collaboration between Target, IDEO and the MIT Media Lab, Food+Future CoLab brings together business, design and technology to create more access to and more trust in our food. As the project developed though, they ran into increasingly complex questions. Take the idea of transparency, for instance. “As consumers, we know less about the food we eat today than at any other time in history,” said Shewmaker. “But do people want to know more?” The answer seems to be yes, sometimes. Is it fat-free? Is it good for the environment? Is it organic? Is it non-GMO? How many food miles has it traveled? Is it gluten-free? Is it real? There’s no one size fits all answer, and these questions reflect the perils of information overload as we try to educate consumers.

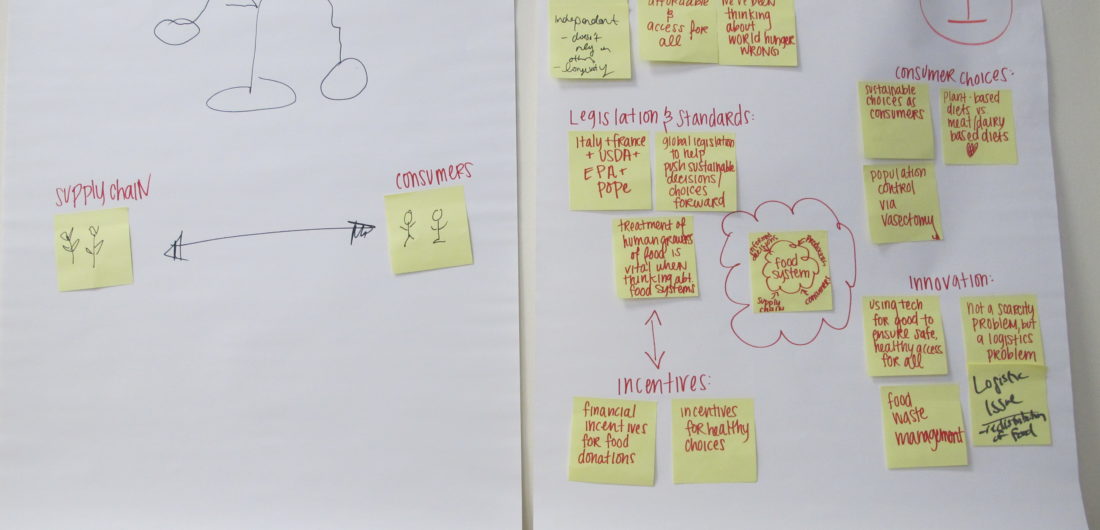

In small groups, we brainstormed ways to define sustainability and shift our food system in that direction. The discussion quickly got heated. “I don’t think we have a food production problem, we have a food distribution problem, and we should focus more on combating food waste,” said one participant. “Yes, we need to pay more attention to food waste, but let’s not forget the world population is also projected to reach 9 billion by 2050,” came a rebuttal. “I don’t want to get too off-topic, but how do we manage population growth?” “As a keystone action with so many other benefits, I cannot think of anything better than encouraging more home cooking. You’ll be healthier, save money, spend time with friends and family, and automatically learn about your food,” I said. Another person interjected, “But what about single moms who don’t have time to cook?” Within our small but opinionated group, we found much to agree on, and even more to disagree on. In the end, time constraints forced us to cobble together a rough outline of our vision for a sustainable food system, with components for consumer choices, technological innovations, and government legislation. “Just remember,” said Overcash. “A revolution has never been started by a government.”

Afterwards, I slipped into the main conference and marveled at a presentation by National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry. “My work is about exploring oceans and sharing what I’ve learned with others,” he said. “I’ve begun more frequently to see horrible things, and I feel a responsibility to share these problems. Our oceans are under assault, but there are solutions.” Skerry went on to show us an experimental farm off Vancouver Island, practicing integrated multitrophic aquaculture. What exactly does that mean? Rather than raising a single species or crop, this farm raises multiple species, which work together in environmentally harmonious ways. For instance, sablefish (or black cod) produce nitrates and waste. So, the farm has scallops growing further downstream, which filter and clean the water. Then, sugar kelp is raised on lines nearby to further consume and break down the excretions from the sablefish. Each item is a profitable crop, and each provides different types of checks and balances for the ecosystem.

When you read the news stories of sea levels rising, stronger and more erratic storms, and mass species extinctions, it is easy to be paralyzed by the doom and gloom. But rather than inaction, we need a paradigm shift to spur action. The Social Good Summit is about realizing that there’s hope for a better future, that people are already working toward this, and that we can all commit to making a difference if we pay attention. As singer-songwriter Cody Simpson concluded in his talk, “Nature cannot speak to you in language, but it can speak to you if you listen.”